On Dominance Terminology: Tracing the History of Master-Slave From GitHub to Sir Francis Bacon

[Nature] is either free and follows her ordinary course of development as in the heavens, in the animal and vegetable creation, and in the general array of the universe; or she is driven out of her ordinary course by the perverseness, insolence, and forwardness of matter and violence of impediments, as in the case of monsters; or lastly, she is put in constraint, molded, and made as it were new by art and the hand of man; as in things artificial. - Sir Francis Bacon, De Augmentis Scientarum (1623)

Keywords/Topics:

- Version Control

- Git

- Linus Torvalds

- Ethnomathematics

- Timeshare Computing

- Shakespeare

- Sir Francis Bacon

- scala naturae

- anthropometry and phrenology

- Social Darwinism

Overview

A few months back, a controversy resurfaced in the world of tech. The controversy centered on the use of language and history at the world’s largest repository for open-source code, GitHub. Developers from around the world had begun to reiterate their opposition to the default “master” branch convention GitHub used in its version control system. This month, after years of inaction, GitHub will officially change its default branch names from master to main. To many, this change is long overdue. But to a significant number of people, the change is unnecessary. Because GitHub does not expressly use the word “slave” in its architecture, these developers argue, the use of master is anodyne. Message boards are still filled with commentators arguing this very point. If the issue of master branches and version control systems confuses you, you’re not alone. In Part I (On Git, GitHub and Master-Slave) more context is given into what can be obscure subjects, providing an explanation as to what GitHub is and how the term “master” has been applied in version control systems.

For now, what can be said is that, despite GitHub having decided to transition to other terminology, a slim few in either party have gone so far as to write about the history of these words as applied to technology. If they had, they would have found that, as far as we know, master-slave language had only entered technological vernacular in the 20th century. Part II (Master-Slave in the 20th Century) elaborates on the best available research to be found on the history of master-slave terminology in the engineering and technological fields during the 20th century. Relying on keywords in patents, I review evidence into what might be the first modern use of master-slave terminology in the engineering context. I also explore which scientific fields began and continue to use “master-slave” terminology.

To truly understand how master-slave terminology could have emerged, requires a deeper exploration of history. For that reason, in Part III (Dominus Machina—The Scientific Revolution and Hierarchical Thinking) a more extensive review of the Scientific Revolution is made. Here I explore how socio-economic uncertainties during the 16th and 17th centuries laid the groundwork for a new hierarchical philosophy, promulgated by popular thinkers such as Sir Francis Bacon, in which man (in the gendered sense) had the divine right to dominate and enslave the earth for the purpose of progress and the accumulation of knowledge. This hierarchical thinking was adapted throughout the centuries to fit contemporaneous social beliefs. From racial hierarchies to anthropometry, phrenology, and Social Darwinism, dominance terminology and hierarchical thinking that emerged in the 17th century had become a tradition of the academic and technological sectors of the English-speaking world.

After reading this essay, I hope it becomes clear why master and master-slave terminology continues to be used in 2020. This post is not meant to rehash a debate about the use of master and master-slave branching. Frankly, it seems clear that the terms should never have been used. Neither is this post meant to characterize all hierarchical thinking as evil. Instead, the aim of this essay is to, respectfully, establish a fuller contextual history about the development of “master-slave” terminology in tech, and hierarchical thought in the sciences more generally. This is a difficult task because there is large portion of history to cover. In this essay, I concentrate on the roots of master-slave terminology in science which comes at the expense of more modern history. In the future, I hope to write more about our recent past.1 More importantly, however, is that this topic matters deeply to many individuals—as it should. It is my hope that I have chosen my words respectfully and made my points accurately. To properly grasp the essence of this history, however, one must first understand the core service GitHub provides.

Part I: On Git, GitHub, and Master-Slave

In the course of a program’s existence, developers often make many iterative changes to their code. Sometimes a change in the code will break the program, or a function, or a feature therein. In such cases, it is often helpful to have access to a previous, working version of the code in which to revert. For this and many other reasons,2 there exists the concept of version control—the recording and management of changes to code and documents.3 Since 2005 a primary tool for version control has been Git—a decentralized version control system (“Distributed Version Control”) in which the historical ledger of program alterations are retained by both remote and local servers. Soon after its open-source release, Git became the most used version control system in the world.4

Helping in the ascent of Git was GitHub.5 Established in 2008, GitHub provided developers using Git’s open-source software a means to host their code in remote repositories—libraries of files and documents—for free, while adding useful features like the ability to collaborate with other developers on the same projects. It also provided premium benefits to commercial ventures. Riding a wave of Big Data integration and open-source use throughout the 2010’s, by 2015 it was estimated that GitHub was worth $2 billion. In 2018 the company was acquired by Microsoft for $7.5 billion in Microsoft stock.

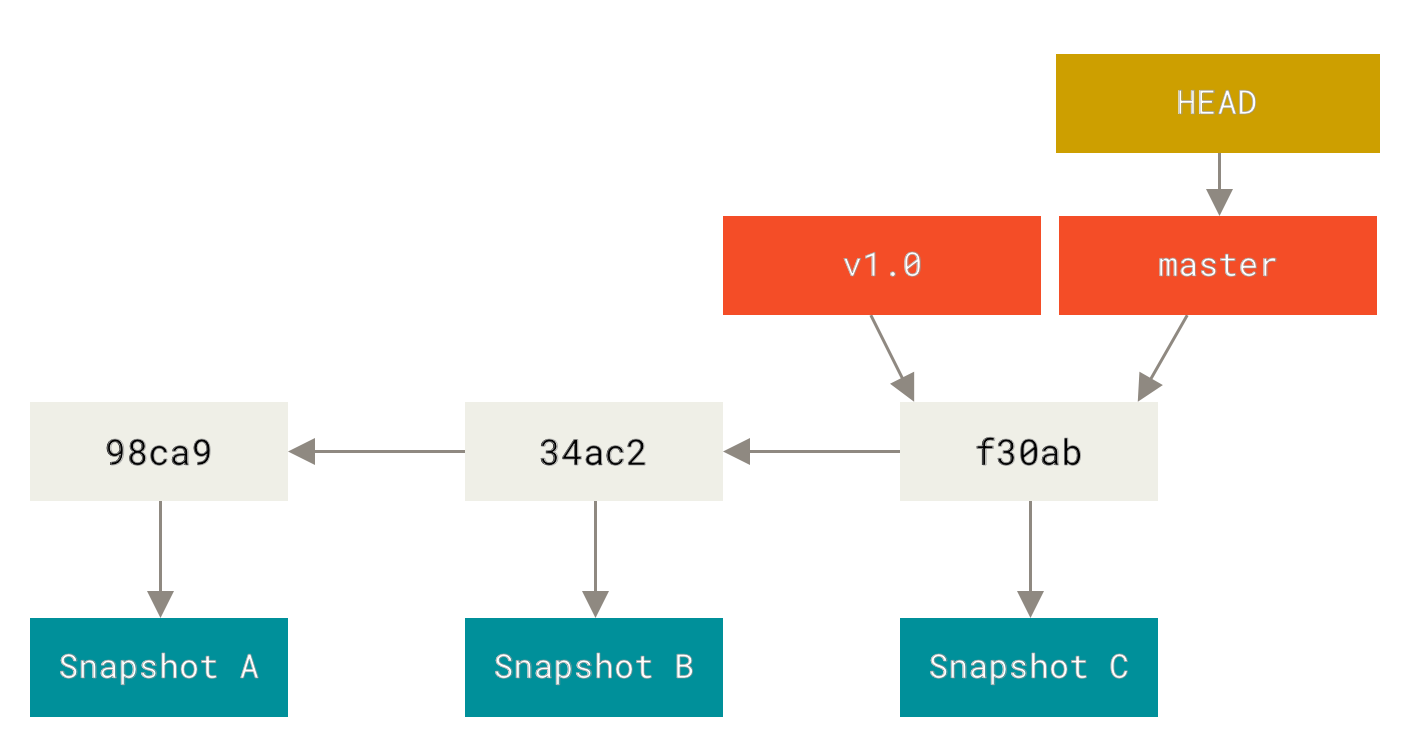

In acquiring GitHub, however, Microsoft also inherited its customs. A key feature of Git, and of GitHub by proxy, is how information is stored. The initial “commit” of data to a repository creates a tree, or hierarchy, of information “snapshots” which are pointed to by a reference variable (called a HEAD). From this tree begins an initial development “branch” under which each new commit of information is stored. In Git, and GitHub, this first branch (there can be many branches) is by default given the name “master.” As the initial branch to each project, the “master branch” has to many become tied to the idea of storing their information hierarchically in GitHub.6 And there’s the rub: for the common use of master to many people—especially people of color—evokes a shameful period in American history and breeds an atmosphere of intolerance and inequality in an already unrepresentative field.

So, is it true? Is the etymological root of master, in this context, oppressive in nature? Working against an anodyne interpretation of master is the common use of “master-slave” terminology in much of the technology sector—context that is often conveniently omitted from justifications about the use of master. For example, it does not take much research to discover that the creator of Git, Linus Torvalds, is known to have sourced the inspiration of Git from a commercial version-control system called BitKeeper. BitKeeper calls its branches and repositories masters and slaves.7 True, there are no “slave” conventions used in Git or GitHub, but this does not indemnify either from their reliance upon the use of master—it simply implies that those who use the term are ignorant of its origin.

For some, this reasoning will fall short: yes, the root of master in Git may originate with the master-slave paradigm, but it is no longer used in this sense—so let’s move on. Commonly left out of this reasoning, however, is an answer to the following question: why use master-slave terminology at all? Why do GitHub, BitKeeper, or any other company for that matter rely on such terms? And, who started using such terminology? To this last question, some have sought an answer. It turns out the use of these specific terms seems to have emerged only in the quite recent past.

Part II: Master-Slave in the 20th Century

In 2007, a fascinating article was published out of the University of Michigan. The article, “Broken Metaphor: The Master-Slave Analogy in Technical Literature”, had a simple conceit: to explore the history of master-slave terminology by studying patents throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. The article’s author, Ron Eglash, a professor of ethnomathematics, had a wider focus than current hot-button issues such as algorithmic bias. Practitioners of the field of ethnomathematics like Eglash study the etymology and social interactivity between mathematics and culture throughout the world. In his article, Eglash was concerned not simply with the use of master-slave, but how the terms were generated.

As far as Eglash could tell, there were no references to master-slave terminology before the American Civil War. The earliest instance he could find occurred in a 1904 patent for a sidereal clock—a timekeeping system to locate celestial objects—by the astronomer David Gill in Cape Town, South Africa. According to the patent’s language, the clock “consists of two separate instruments: (a) a pendulum (swinging in a nearly airtight enclosure maintained at uniform temperature and pressure) and (b) the ‘slave clock’ with wheel train and dead-beat escapement.”8 The association of master-slave terminology with South Africa may sound nefarious due to its history, but, to Eglash, we should consider the following:

Although today we associate South Africa with the racism of apartheid, at the time Gill wrote slavery had been outlawed in the Cape Colony for over sixty years, and Cape Town itself had been the home port of the Royal Navy’s West African Squadron, which was deeply involved in the suppression of the slave trade in the mid-nineteenth century. Gill’s biography gives no indication that he had a positive view of slavery, nor that he was a particularly enlightened colonialist when it came to that. His wife Isobel’s memoir of their time spent with primarily African staff on Ascension Island similarly betrays no pro-slavery inclinations; on the contrary, it records her increasing respect for the Kru sailors. If Gill thought about the social echoes of the master-slave metaphor, it would have been with disapproval.

In short, solely looking to the immediate context of its environment, there is little evidence to believe that Gill’s use of master-slave came from a oppressive place. And yet, throughout the 20th century master-slave terminology emerged in an increasing number of fields: from horological [clock] engineering, to photography9, hardware engineering, locomotives, and mathematical methods such as Finite Element Analysis.

In computer engineering, the first appearance of master-slave seems to have occurred, unsurprisingly, in 1964, by the Dartmouth timeshare computing team (for more on timesharing systems see my article: On The Origin of Time-Sharing Computers, Round-Robin Algorithms, and Cloud Computing). According to computer scientists John Kemeny and Thomas Kurtz, the timesharing system—which was a means by which programmers could seamlessly submit code to a central processor—required “…all computing for users [to take] place in the slave computer, while the executive program (the ‘brains’ of the system) [would reside] in the master computer. It [would thus be] impossible for an erroneous or runaway user program in the slave computer to ‘damage’ the executive program and thereby bring the whole system to a halt.”10 Thus in computing, as in other fields, the origin of master-slave seems to have been in describing a relationship, or hierarchy, between two systems.

In fact in each field one examines, the use of master-slave terminology encompasses more than the singular words themselves but their use as a relation; in each instance a slave process is subservient to the master process. And, perhaps it is true that one process yields to the other, but is it not curious, if even concerning, that our language cannot but revert to what is tantamount to colonial language to explain hierarchies? Indeed, it says a great deal about how we have developed our cultural and linguistic relationships to ordered systems that the master-slave paradigm is so prevalent. In fact, as will be argued, it is our ill-matured relationship to hierarchies that explains how the master-slave paradigm could have emerged in the first place. As will be seen in the next and final section, the origins of dominance-terminology such as the use of master-slave took root during the Scientific Revolution—the reverberations from which influenced cultural phenomena and in turn shaped our language and thinking about hierarchies.

Part III: Dominus Machina—The Scientific Revolution and Hierarchical Thinking

In the 16th and 17th Century, Western civilizations—and, in particular, English speaking societies—underwent a period of sustained cultural and economic transition.11 The discovery of the Americas brought with it stories of a capricious “new world”: a land brimming with bountiful resources that easily and often turned to cannibalism, chaos, and dread.12 To many, including the Governor of Plymouth Colony William Bradford, there was no other way to see this new world but as “a hideous & desolate wilderness, full of wild beasts & wild men.”13 Meanwhile, in the “old world”, censures against nature were just as dark. In Vanity of Arts and Science (1530), Heinrich Agrippa, arguably the most influential occultist of the period, argued that after man’s Fall from the Garden of Eden, nature had become an uncontrollable wilderness, producing “…nothing without our labor and our sweat, but deadly and venomous, … nor are the other elements less kind to us: many the seas destroy with raging tempests, and the horrid monsters devour: the air making war against us with thunder, lightning, and storms; and with a crowd of pestilential diseases, the heavens conspire our ruin.”14

These negative views of nature were reflective of the larger socio-political uncertainties of the time. In England and Western Europe, feudalistic systems were giving way to mercantile capitalism, religious wars were on the rise, and the Reformation began to question the dominant Catholic hierarchy.15 With these seismic changes to Western systems also came a new science which served to further exacerbate a sense of displacement. From the new science came a new view of the universe, influenced by Nicholas Copernicus’s 1543 heliocentric model, shifting the story away from an ordered universe with Earth at its center to that of Earth as one among many distant, sun-orbiting planets.16

These many changes to the social, religious, and geographic order engendered philosophical questions about which artists and intellectuals of the time began to grapple. The idea of an ordered world unraveling—one in which chaos and uncertainty affected even the planets—concerned the likes of Shakespeare’s Ulysses in Troilus and Cressida (produced 1602) who expounded upon the dangers of removing a degree of hierarchy:17

What honey is expected? Degree being vizarded,

The unworthiest shows as fairly in the mask.

The heavens themselves, the planets and this centre

Observe degree, priority and place,

Insisture, course, proportion, season, form,

Office and custom, in all line of order;

And therefore is the glorious planet Sol

In noble eminence enthroned and sphered

Amidst the other; whose medicinable eye

Corrects the ill aspects of planets evil,

And posts, like the commandment of a king,

Sans cheque to good and bad: but when the planets

In evil mixture to disorder wander,

What plagues and what portents! what mutiny!

What raging of the sea! shaking of earth!

Commotion in the winds! frights, changes, horrors,

Divert and crack, rend and deracinate

The unity and married calm of states

Quite from their fixure! O, when degree is shaked,

Which is the ladder to all high designs,

Then enterprise is sick! How could communities,

Degrees in schools and brotherhoods in cities,

Peaceful commerce from dividable shores,

The primogenitive and due of birth,

Prerogative of age, crowns, sceptres, laurels,

But by degree, stand in authentic place?

Take but degree away, untune that string,

And, hark, what discord follows!

To Ulysses, and to many other well-connected individuals, a weak hierarchy meant experiencing an unacceptable fragility in a world that was sustained by hierarchies: both social and celestial. In reality, these hierarchies about which Shakespeare wrote were maintained not simply for a sense of safety for the elite, but also for a sense of self in the macrocosm.18 By disrupting the order, many people’s sense of place and purpose became uncertain.

In the widened gap of uncertainty amplified by the new science fit the seeds of a novel philosophy that would be familiar to modern eyes, but that would contain in it an implication that time has tampered. At the forefront, evangelizing this philosophy, was Sir Francis Bacon and his contemporaries—the original boosters.19 To Bacon and company it was clear that it should be man’s goal (in the sense of gender) to dominate nature—to dissect it piece by piece—so that man might control nature and return it to the order that had been missing since man’s Fall from the Garden of Eden. Unlike Agrippa’s view of the world, to Bacon and his acolytes, nature was knowable and insofar as it was knowable it was man’s right to know it and control it—the Divine was order and hierarchy, after all. And, since man was “like unto God”, it was his duty to impart this order and hierarchy upon the world so that “the human race [could] recover that right over nature which belongs to it by divine bequest.”20 After all, what was the Garden if not ordered nature? And was this not the paradise that man had lost? The idea that nature was atomistic and rebuildable was reflected by the influential natural philosopher Johannas Kepler who, in 1605, wrote in a letter to a friend, “My aim is to show that the celestial machine is to be likened not to a divine organism but to a clockwork.”21

This new philosophy was a marked shift from the past. Whereas in the medieval era, nature was seen as something to be appreciated but left unstudied, the philosophy Bacon espoused provided man both the opportunity to overcome the uncertainties that had been thrust onto him, and the justification “…to establish and extend the power and dominion of the human race itself over the universe.”22. All one had to do was steel oneself for what it required. Wrote Bacon, “For you have but to follow and as it were hound nature in her wanderings and you will be able to when you like to lead and drive her afterward to the same place again.” Wherever knowledge lay, even if in sorceries and witchcrafts, then “a useful light may be gained, not only for a true judgment of the offenses of persons charged with such practices, but likewise for the further disclosing of the secrets of nature. Neither ought a man to make scruple of entering and penetrating into these holes and corners, when the inquisition of truth is his whole objective.” Furthering this point, Bacon wrote, “For like as a man’s disposition is never well known or proved till he be crossed, nor Proteus ever changed shapes till he was straitened and held fast, so nature exhibits herself more clearly under the trials and vexations of art [mechanical devices] than when left to herself.”23

To know nature, to learn what God had made, required the torture and dismantling of nature to its requisite parts (“the uniting and disuniting of natural bodies”), to be known and recreated by man, for that was the rightful hierarchy of the world. In Bacon’s words, “I [Bacon] am come in very truth leading to you nature with all her children to bind her to your service and make her your slave.” Far be it from the scientist to shy away from this role or to consider the “inquisition of nature is in any part interdicted or forbidden.” Only by staging this inquisition into nature could “the narrow limits of man’s dominion over the universe [reach] to their promised bounds.” But the scientist had “…no right to expect nature to come to [them]. Nature must be taken by the forelock being bald behind. Delay and subtle argument permit one only to clutch at nature, never to lay hold of her and capture her.”24

In this new man-nature ideology proffered by Bacon, accrued knowledge through dominance was paramount.25 Whereas once humanity was seen as apart from a wild and uncontrollable nature, Bacon and his contemporaries now argued that the world was a hierarchy lost—that only when man reclaimed the right of supremacy divinely bestowed, would order and prosperity be rekindled. This philosophy, though originating in distant centuries past, has stood the test of time—altered, yes, into different iterations and forms, but lasting all the same. One need only look to our research institutions and labs.

In New Atlantis (1627),26 his last writing published posthumously, Bacon weaves an allegorical and technocratic vision of what humanity’s utopian future would look like were they to adopt his new philosophy: one where science would be revered on par with religion. The setting of Bacon’s New Atlantis society was the town of Bensalem, which had adopted the customs Bacon attributed to progress. At the center of the town’s successes was its research institution, Salomon’s House, which operated in place of a political apparatus in Bensalem. As historian of science Carolyn Merchant has described the role of Salomon’s House: “Decisions were made for the good of the whole by the scientists, whose judgment was to be trusted implicitly, for they alone possessed the secrets of nature. Scientists decided which secrets were to be revealed to the state and which were to remain the private property of the institute rather than becoming public knowledge.” Merchant goes on to argue that “Bacon’s ‘man of science’ would seem to be a harbinger of many research scientists. Critics of science today argue that scientists have become guardians of a body of scientific knowledge, shrouded in the mysteries of highly technical language that can be fully understood only by those who have had a dozen years of training.”27 If the scientists of Salomon’s House were at the top of the social caste system, they also maintained an internal hierarchy too, with research tasks being divvied by “Father” scientists to novices and apprentices based on merit and experience, not unlike modern graduate programs. Indeed, within Salomon’s house, each matter to be researched and controlled (mining, plants, weather, etc.) was divided into its own “laboratory” program in Bacon’s imagining.

Far from being an isolated, fictional vision of the future, Bacon’s writings in New Atlantis inspired his followers and contemporaries to make real his vision, establishing the oldest scientific and research society in the world, the Royal Society found in November of 1660. Nor did Bacon’s influence cease at the research institute. Philosophers of the 17th century continued to expound on man’s supremacy over nature that Bacon and his contemporaries advocated. In Descartes’ 1636 Discourse on Method, the philosopher writes that researchers could “render [themselves] the masters and possessors of nature” were they to know deeply the mechanistic process of craftsman and artisans.”28 While in 1661 the philosopher and chemist Robert Boyle mused on the difference between knowing and dominating nature, arguing that “there are two very distinct ends that men may propound to themselves by studying natural philosophy [science]. For some men care only to know nature, others desire to command her … to bring nature to be serviceable to their particular ends, whether of health, or riches, or sensual delight.”29

If in these philosopher’s words there seems to be an undertone of sexual control and dominance, that is because there is. To people then, as now, nature had long been associated with life and femininity. Unlike the past, however, the new science and philosophy of the time argued for man’s right to experiment and exploit natural resources, despite nature’s protests. The supremacy of the quest for knowledge is still contained in sexually implicit language today in phrases such as “hard facts,” “penetrating mind,” and “the thrust of his argument.”30 In fact, it was the very hierarchical norms that Bacon and his contemporaries established, both the normative language they used and the practices they advocated for the purpose of progress, that have lasted to this day.

But it would also be a simplification to assert that the path from the Scientific Revolution to our contemporary view of hierarchies is direct. Unfortunately, to give proper justice to the many iterations of hierarchical value systems that developed since the 17th century would require more than a blog post. What can be said is that the path from the 17th century has certainly been winding. Later in that very century, philosophers and scientists continued their shift in language and thinking of the world as something closer to a machine—such as Decartes’ bête machine (animal machine) theory, to name a well-known example—reflecting the many machines that emerged from the time. A brief list of 16th and 17th century inventions that would be familiar to us today includes: lift and force pumps, cranes, windmills, geared wheels, flap valves, chains, pistons, treadmills, under- and overshot watermills, fulling mills, flywheels, bellows, excavators, bucket chains, rollers, geared and wheeled bridges, cranks, elaborate block and tackle systems, worm, spur, crown, and lantern gears, ratchets, wrenches, presses, and screws.31 With so many inventions, fundamental to building systems of engineering and commerce, it should come as no surprise Bacon’s philosophies were adapted alongside them. As innovations and socio-economic changes continued throughout the centuries the dominance perspective would alter to fit the gained knowledge of the times, but the fundamental idea, that it was man’s right to dominate the Earth for the goal of progress.

Of the most significant changes in hierarchical value systems since the 17th century, two adaptations to the Baconian hierarchical program stand out: the advent of slavery and racial hierarchies; and the theory of evolution, anthropometry, and Social Darwinism. Common among the arguments of those who defended slavery was language and thinking akin to that seen during the Scientific Revolution. Michael Renwick Sergant, a Liverpool merchant, is recording having argued whether the enslaved, living “in a well regulated plantation, under the protection of a kind master, do not enjoy as great, nay, even greater advantages than when under their own despotic governments.” Others began to reach to the past for ways to understand and justify the present. Using classical Greek writings about the scala naturae (Scale of Nature)—a natural hierarchy of all living things—these proslavery ideologists sought to make concrete the idea of the term “race” and further sought to establish the idea that those of African descent were naturally and unalterably lowest among these “races.” Whereas in the past these ideas would not likely have held muster, the fact that dominance hierarchies were already ingrained in modern perceptions of the world made it easier for racial hierarchical thinking to take root in Western societies—societies which already had an active economic incentive to believe it.

The advent of the theory of evolution did not help matters. With the idea of racial hierarchies firmly entrenched even in scientific circles, academics took to trying to discover why and how those of African descent could so fundamentally differ from those of European descent. Naturally, the academics took to measurements as a means of justifying their false assumptions. During the mid to late 19th century, and the early 20th century, the practice of anthropometry (the use measurement of the human body and proportions) and specifically phrenology (the pseudo-scientific use of anthropometry to justify racist predispositions), gained favor among proponents of race hierarchies. Using the language of science to propel culturally fostered norms, these academics generated thousands of averages, means, and standard deviations with which to describe, summarize, and categorize the races towards certain narratives—ironically, often without consideration for the how characteristics would evolve over time. To these practitioners, race was a hierarchy, and using the theories of Bacon, and now of Darwin, they sought to prove their assumptions.

Anthropometry and phrenology did not end at the research institution, however. The theory of racial hierarchy and the theory of evolution had entered into the already volatile socio-economic landscape of the mid to late 19th century which, as in the 17th century, was undergoing seismic technological and social changes. As these ideas gained in popularity, so too did ideas that predated even Darwin. Social Darwinism (as it would come to be called), or the idea that social classes were themselves racially and evolutionarily superior, was an idea that predated Darwin. Introduced by Herbert Spencer, the ideas of competition, the struggle for existence, and survival of the fittest were used to justify the state of social inequality. Spencer further argued that, as a matter of science, governments should not support through policies or charity those at the inferior end of the hierarchy, for they would soon die out. Joining Spencer, of course, were the writings of Francis Galton (cousin of Charles Darwin) who also advocated hierarchical thinking. Mining data to justify his predispositions, Galton published books such as Hereditary Genius which argued that the minority upper-class of England had disproportionately produced more great men compared to other social classes.32

By this point, at the end of the 19th century, it should be clear how it came to be that that someone like David Gill—with no explicit history of racism—would use master-slave terminology to describe the mechanical systems of his sidereal clock. Such language and thinking had not ended in the 17th century, but had in fact expanded, adapted, and lasted in the norms and practices of the scientific and social ethos of the times. Hierarchical terminology and value systems lasted because the implicit assumption had been that nature is usufruct, and so too are any technologies or people that need to be used in the name of progress. This language didn’t start with Gill and, as has been shown, it did not end with him either. Throughout the 20th century, hierarchical language like master-slave had been applied to many areas of technology, including computer science.

That one would find master-slave terminology in version control systems in 2020 is less surprising than is the idea that this language came from nowhere, or that its use was not part of a larger history. Whether people today need to recoil at the use of master-slave language in technology is not for me to say. Personally, I find the language pointless and imprecise when there are other, perfectly valid conventions to use such as parent and child, or main and secondary. More important, however, is the understanding that the use of technical and non-technical language emerges from norms and practices of the times. If people truly care about people of color, or any minority-status individuals, treating them with consideration and providing them fair pay might be an even more worthwhile place to start—language norms would be sure to soon follow. As for the history of the master-slave convention, after researching the subject, I think there is still a book’s worth of fascinating history left to write that I may one day attempt to accomplish.

Endnotes

-

If you were taught using master-slave terminology during the course of your education—or if you have other relevant material you would like to share for my research—I would love to hear from you. Please reach out to me at benjaminlabaschin@gmail.com. ↩

-

This is not to ignore the many other reasons for the existence of version control or GitHub, including collaboration, branching code, etc. ↩

-

This process is not actually unique to computer programmers. Consider college textbook, for example. Oftentimes there will be many versions of the same book. ↩

-

In 2011, a Microsoft survey of 1000 developers found Git had overtaken other version control systems as the most popular. Other surveys on version control systems I’ve found come from StackOverflow in the years 2015, 2017, 2018. Git ranked #1 each year for tens-of-thousands of respondents, eventually so out-pacing the competition it seems the website has ceased asking respondents which version control system they use. ↩

-

There are many other reasons for Git’s assent, besides GitHub, including its use of snapshots and pointers. ↩

-

It’s worth noting that one can change the default naming convention to their Git Branches manually.However, most developers stick with the default naming conventions. ↩

-

The research in this paragraph was inspired by this chat-room post by Bastien Nocera. ↩

-

Located on page two of Eglash, see also Eglash footnote 3. ↩

-

The earliest use of the term “slave flash” I could find was in 1953 in a photgraphy guide by Heinrich Freytag seen here ↩

-

Located on page three of Eglash, see also Eglash footnote 8; John Kemeny and Thomas Kurtz, “Dartmouth Timesharing,” Science 162, no. 3850, 11 October 1968, 223–68. ↩

-

The content of this section adapts many of the arguments from and contents of Carolyn Merchant’s The Death of Nature, which I cite throughout the post. In the painting above, Blake used “Ancient of Days” as cover art for his Europe a Prophecy. The man depicted is Urizen, a mythological character of Blake’s. Urizen represented a dominant, satanic force of reason and law whose goal was to make uniform all of mankind. Here Urizon holds a compass and measures what seems to be the void below him. During Blake’s final days, he continued to work on a commissioned version of this piece while sick in bed. See more here ↩

-

Recall that prominent among the religious of the time was the idea of the Devil residing in attractive and seemingly beneficial matters. The fact that the “new world” could be bountiful and devilish was not lost upon Pilgrims. Carolyn Merchant, The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution San Francisco: Harper & Row (1989): 131. ↩

-

Again, note the dissonant mentality the pilgrims retained having stumbled upon a wilderness full of flora and fauna, while yet maintaining the conviction that the place was desolate. To the pilgrims, clearly an unordered wilderness, in the European sense, was desolate, despite being full of life. A fuller version of the quote from Governor William Bradford (1620) can be found here. ↩

-

Merchant The Death of Nature (1989): 185. ↩

-

Carolyn Merchant, “Secrets of Nature: The Bacon Debates Revisted,” JHI, 147, (2008); Brian Vickers, “Francis Bacon, Feminist Historiography, and the Dominion of Nature,” JHI, 69 (2008) ↩

-

Note that I pluralize Western Civilizations. This is because there were many dissonant cultures through which new knowledge was filtered. In England, there was a particular dearth of original philosophy until Sir Francis Bacon. There were the Aristotelian Scholastics, who focused upon rhetorical superiority; the Humanists, whose concerns romanticized nature, but actively disdained any knowledge of it; and the Occultists, where Bacon fell, who sought magical powers over natural processes. See Francis Bacon. ↩

-

Merchant The Death of Nature (1989): 128-129; William Shakespeare, Act 1, Scene 3, “Troilus and Cressida”, The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (2019). ↩

-

There’s a reason Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy characterized Heaven, Hell, and Purgatory as hierarchies. ↩

-

Boosters were futurists and speculators on the Western Frontier of the early 19th Century who hyped the latest science to try to convince investors where the next great urban city of the West would be. William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West New York: W.W. Norton, 1997: 34. ↩

-

Merchant, The Death of Nature (1989): 172. ↩

-

ibid: 128-129. ↩

-

ibid: 172. ↩

-

ibid: 168-169. ↩

-

ibid: 170-172. ↩

-

This perspective was of course justified through the bible. Particularly in Genesis 1:26, “And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.” ↩

-

There are differing account about when New Atlantis was published. ↩

-

Merchant, The Death of Nature (1989): 180-182. ↩

-

ibid: 188. ↩

-

ibid: 189. ↩

-

ibid: 171. ↩

-

ibid: 2-3. ↩